Top

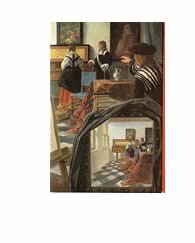

row - Robert Ayton, from Tricks and Magic 1969;

last from Toys and Games We Make 1966.

Second

Row - John Berry, from The Nurse 1963; Martin Aitchison

from Games We Like 1964; J.H.Wingfield, Things

We Do 1964; Robert Ayton, from Boys and Girls 1964

Third

Row - John Berry. from Cub Scouts 1970; J.H.Wingfield,

from The Holiday Camp Mystery 1966; G.Robinson Things

to Make 1963; Martin Aitchison, from Great Artists 1970

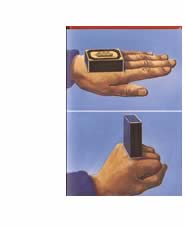

These

are individual images extracted from their sequences within the

books, taken away from the explanatory texts printed opposite. Unfair?

Oh yes, but the isolation intensifies the solidity, the dignity,

the 'Chinese pitch of oddity'. I admire the quality of paint that

is dead to the touch. Magritte, Jared French, Joseph Southall etc.

There is no need for shimmering brushstrokes, and the cult of painting a

premier coup.

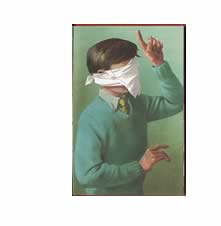

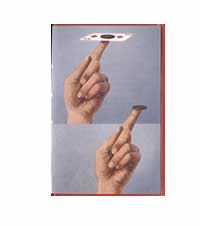

The compositions are predictable within the house style, but full

of a chilled formality which I find oddly appropriate for the reminiscences

of childhood. Particularly magical are the semi-educational illustrations

of magical tricks performed by infants of considerable gravity.

Quickness of hand? Not here. A slow and steady passage of objects

from one dimension to another.

It is

lazy thinking to believe that the illustrators worked 'with tongue

in cheek'. I hope they didn't. It would undermine the ritalistic

nature of the scenes, the loading of the ambulance, the parade of

swimmers, the point of view of Vermeer's camera obscura, the perpetually

hovering moppet against a clear summer's sky.

There

are objections made on a regular basis that the Ladybird books did

not represent the nation as a whole, the poverty and lack of opportunity

of the working classes, the new ethnic majorities, the presence of

crime and nuclear anxieties. All this is true for those of

you who believe the primary role of the books is to instruct and

reinforce the nature of Society.

I would

counter that the books accurately reflect my life in Handforth and

Watford. And even when they don't, provide a magical prism with

as much terror as nostalgia. Watching David Lynch's films there

are moments when a gesture or an inanimate object take on a particular

significance for which you just can't give account.

In the

three galleries I will attach the texts to the images so you don't

feel thwarted.The oddness of message and atmosphere is sustained

over the double page.

Champfleury

declared Pre-Raphaelite paintings as images of "a Chinese pitch

of oddity" (c1859), an admirable perspective given his limited exposure

to English painting. |